- Today

- Holidays

- Birthdays

- Reminders

- Cities

- Atlanta

- Austin

- Baltimore

- Berwyn

- Beverly Hills

- Birmingham

- Boston

- Brooklyn

- Buffalo

- Charlotte

- Chicago

- Cincinnati

- Cleveland

- Columbus

- Dallas

- Denver

- Detroit

- Fort Worth

- Houston

- Indianapolis

- Knoxville

- Las Vegas

- Los Angeles

- Louisville

- Madison

- Memphis

- Miami

- Milwaukee

- Minneapolis

- Nashville

- New Orleans

- New York

- Omaha

- Orlando

- Philadelphia

- Phoenix

- Pittsburgh

- Portland

- Raleigh

- Richmond

- Rutherford

- Sacramento

- Salt Lake City

- San Antonio

- San Diego

- San Francisco

- San Jose

- Seattle

- Tampa

- Tucson

- Washington

Marietta Today

By the People, for the People

Toxic Oil Wastewater Buried Underground Poses Serious Risks

Historic documents reveal EPA knew injection wells were unsafe, but industry pressure led to lax regulations

Published on Feb. 12, 2026

Got story updates? Submit your updates here. ›

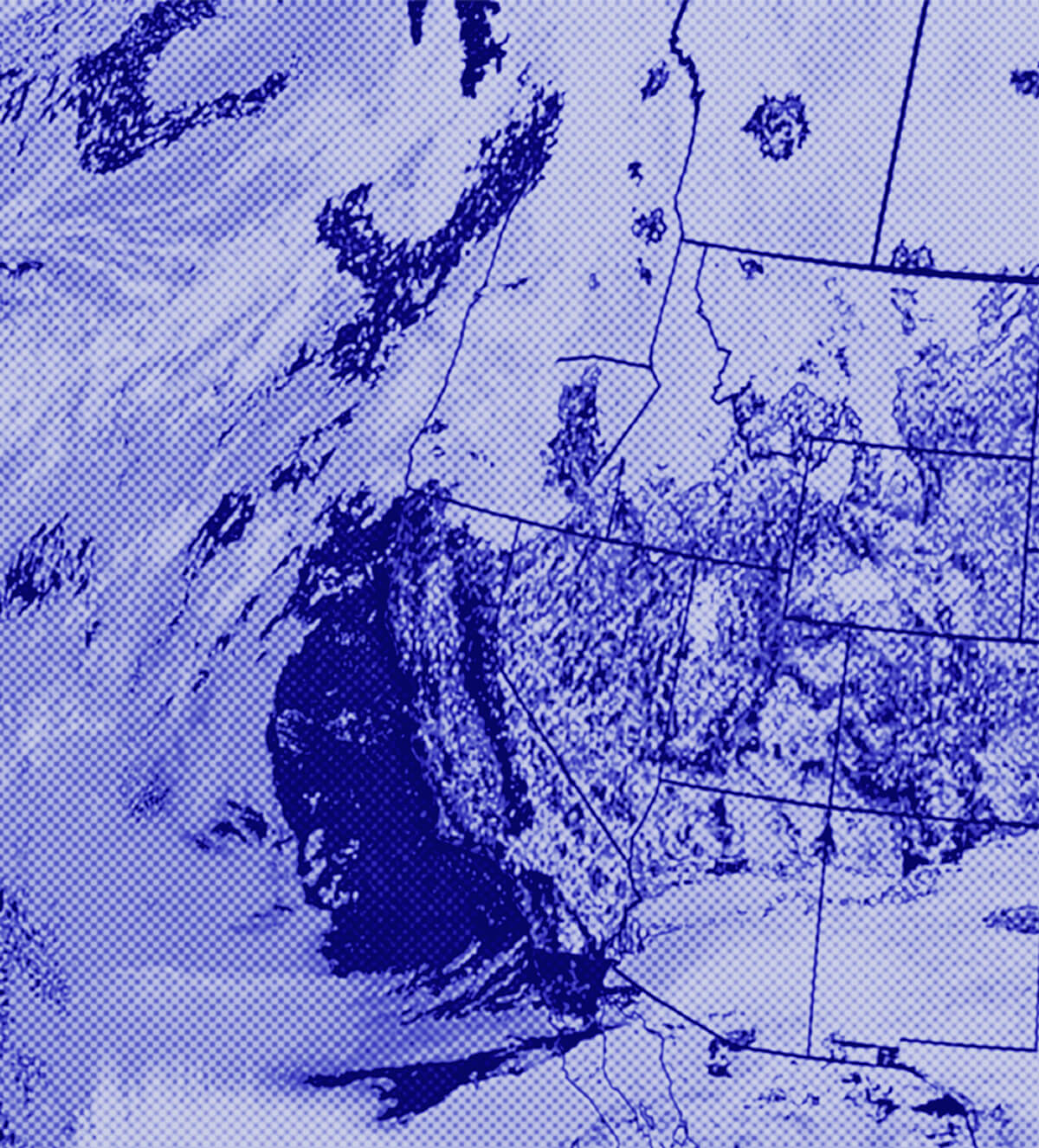

A cache of government documents dating back nearly a century shows the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) knew long ago that injecting toxic wastewater from oil and gas production underground was dangerous, putting drinking water and other mineral resources at risk of contamination. Despite these concerns, the EPA enabled the widespread use of injection wells for waste disposal, driven by industry pressure and lawsuits. The oil and gas industry now disposes of over 1 trillion gallons of wastewater annually through injection wells, raising growing concerns about earthquakes, groundwater pollution, and other environmental threats.

Why it matters

The oil and gas industry's reliance on injection wells for toxic wastewater disposal has created a profound pollution crisis across the country, with documented cases of contaminated drinking water, damaged property, and environmental damage. This highlights the need for stricter regulation and oversight of injection wells, as well as the development of more sustainable waste management solutions for the industry.

The details

The documents show that as early as the 1970s, government researchers and officials were aware of the risks of using injection wells for waste disposal, including the potential for groundwater contamination, earthquakes, and damage to underground oil and gas deposits. However, industry pressure and lawsuits led the EPA to weaken regulations and hand over control of injection wells to state regulators, who have often been influenced by the oil and gas industry. Today, the U.S. has over 181,000 active injection wells, disposing of over 1 trillion gallons of toxic wastewater annually, with growing evidence of environmental damage and public health risks.

- In 1950, there were just four industrial injection wells in the United States.

- In 1967, there were 110 industrial injection wells in the United States.

- In 1972, the passage of the Clean Water Act drove a massive growth in underground waste disposal through injection wells.

- In June 1980, the EPA began regulating injection wells under the Underground Injection Control (UIC) program.

- In the 1980s, the EPA faced multiple lawsuits from industries, including oil and gas, mining, and steel, which complained the injection well regulations were too complex and costly.

The players

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

The federal agency responsible for regulating and overseeing the use of injection wells for waste disposal, despite early concerns about the safety and long-term impacts of this practice.

Oil and Gas Industry

The industry that produces over 1 trillion gallons of toxic wastewater annually and has heavily lobbied to weaken regulations on injection wells, which are the primary method of disposal for this waste.

David Dominick

The commissioner of the Federal Water Quality Administration (which would later be merged into the EPA) who in 1970 warned that injection was a short-term fix to be used with caution and 'only until better methods of disposal are developed.'

Stanley Greenfield

The EPA Assistant Administrator for Research and Monitoring who in 1971 stated that deep-well injection is 'a technology of avoiding problems, not solving them in any real sense' and that 'we really do not know what happens to the wastes down there' and 'we just hope.'

John Ferris

A USGS hydrologist who in 1971 warned that wastewater would inevitably escape the injection zone and 'engulf everything in its inexorable migration toward the discharge boundaries of the flow system.'

What they’re saying

“We really do not know what happens to the wastes down there. We just hope.”

— Stanley Greenfield, EPA Assistant Administrator for Research and Monitoring (Underground Waste Management and Environmental Implications* symposium)

“Where will the waste reside 100 years from now? We may just be opening up a Pandora's box.”

— Orlo Childs, Texas petroleum geologist (Underground Waste Management and Environmental Implications* symposium)

“It is clear that this method is not the final answer to society's waste problems.”

— Theodore Cook, American Association of Petroleum Geologists (Roundup of *Underground Waste Management and Environmental Implications* symposium presentations)

What’s next

The judge in the case filed by Ohio oil and gas operator Bob Lane will decide on Tuesday whether to allow the case to proceed to trial. The outcome of this case could have significant implications for the future regulation and oversight of injection wells in Ohio and potentially other states.

The takeaway

The historic documents uncovered in this investigation reveal that the EPA and other government agencies have long been aware of the serious risks and environmental threats posed by the oil and gas industry's reliance on injection wells for toxic wastewater disposal. However, industry pressure and influence have led to lax regulations and inadequate oversight, allowing this practice to continue unabated and creating a growing pollution crisis across the country. This highlights the urgent need for stricter regulations, improved monitoring, and the development of more sustainable waste management solutions for the oil and gas industry.